The areas of Fitzroy and Collingwood in the late 1800’s was a far cry from the restaurant & boutique lined streets that we know. Poverty and crime were rampant, and unwed or deserted mothers, in particular, had few resources to make ends meet. Many were forced by circumstance to hand over their child – on a casual or semi-permanent basis for a fee – to an unregulated child minder. Something akin to what we know as in-home day-care. These child minders became known as baby farmers.

Whilst the practice of baby farming was becoming more prevalent, there were reputable institutions opening their doors to address this social issue. In 1877 the Victorian Infant Asylum started in Fitzroy, later moving to the corner of Vale and Berry Streets, East Melbourne when it became the Berry Street Babies Home and Hospital. But such institutions were few and this left countless women with nowhere to turn.

As a result, baby farmers continued to flout the law and it soon became evident that babies were dying due to neglect, starvation and shockingly murder. Sometimes, mothers would arrive to visit their baby, only to find the childminder had fled, having sold the infant in her care for an extortionate sum.

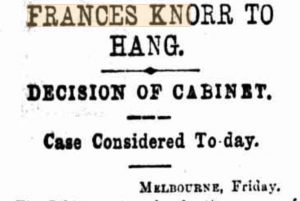

Public outrage at the practice grew over the next decade and then in late 1893 came the case of Frances Knorr, the “Baby Farmer Murderess”.

At the height of the 1890s depression, and after her husband Rudi was gaoled, Frances Knorr was left destitute with a toddler to support. She took up with another man but, when he left her pregnant, she did what many poor women did at this time – childminding.

In September 1893 a Brunswick resident was planting a garden bed when he discovered the body of a new-born baby, later identified as three-week old Gladys Crighton. Neighbours pointed out another nearby house rented by Knorr and police found the bodies of two more infants. Although a cause of death was never established for Gladys, there were clear indications of murder by strangulation and suffocation of the other infants. Knorr had fled to Sydney but was soon found and extradited to Melbourne.

Knorr’s character was put on trial: She was of ‘loose habits, immoral character and hardened nature’, and held rowdy parties, attended by ‘fast young men and women’.

The evidence against Knorr, however, was far from conclusive. Knorr insisted that Gladys had died of convulsions and that she had buried the body in the garden because she ‘got frightened’.

It died from convulsions and not from any ill treatment on my part. I swear that I did everything in my power to resuscitate it… thought of going to the police first but got frightened. Then I thought “I will bury it”.

Presiding over the trial, Justice Holroyd acknowledged in his summary that there was ‘no direct proof of killing’, but the jury convicted her anyway, perhaps as a lesson to others. Public opinion was running high against Knorr at the time, with public parades demanding the death penalty. Crowds chanted ‘Hang Mrs Knorr!’ and ‘Death to the baby killer!’

Whilst the media howled for blood, there were some who petitioned against the sentence – claiming her crime was motivated by poverty rather than immorality. Knorr’s husband Rudi’s plea for clemency to the Governor claimed that his wife was an epileptic, given to severe fits that sometimes led to irrational impulses and long bouts of staring blankly into space. The strongest protest was made by the hangman, William Perrins. Two nights before Knorr’s execution was scheduled ‘Jones the Hangman’ committed suicide by cutting his own throat. All because of his “unwillingness to execute Mrs Knorr, the baby farmer… shrinking from the contemptuous jeers and the persecutions of his neighbours, who, he believed, would be still more hostile if he hanged a woman”.

On the eve of her execution, and having turned to God, Frances Knorr confessed to killing two of the babies discovered:

… upon the two charges known in evidence as No. 1 and 2 babies I confess to be guilty. Placed as I am now, within a few hours of my death, I express a strong desire that this statement be made public, with the hope that my fate will not only be a warning for others, but also act as a deterrent…

The city’s health officer, Dr Neil, told a royal commission in 1893 that, of about 500 post-mortems he had performed on child bodies, more than half indicated murder. Indeed there was a suggestion that Frances Knorr could have killed up to 13 babies during her years as a childminder.

Frances Knorr was executed by hanging at 10am on 15 Jan 1894 at Melbourne Gaol. Her death mask can be viewed there.

Images: Berry St infants. Frances Knorr.

—————–

References

https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/frances-knorr-the-brunswick-baby-farmer/

https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/a-diverse-state/felon-families/frances-knorr/

https://murderpedia.org/female.K/k/knorr-frances.htm